What is the cost of megachurches’ “clever” marketing?

Megachurches remove traditional Christian symbols from their unique brand identities to appeal to a mass audience, while failing to show people their true convictions.

Screenshot of the home page of Churchome’s website

Few conversation topics right now seem to set more fire to the group chat than cults—our fascination with them being targeted in recent documentary series like HBO Max’s The Way Down: God, Greed and the Cult of Gwen Shamblin, examining the life and problematic ministry of Remnant Fellowship Church founder Gwen Shamblin, and Amazon Prime’s LuLaRich, which tells about the meteoric growth and even faster plummet of multi-level marketing retail company LuLaRoe.

In both docuseries, most prominently in The Way Down and surprisingly so in LuLaRich, religion plays a role in creating the environments that allow the documentaries’ focal communities to be thought of as cults. Raised in a Church of Christ family, Gwen Shamblin developed her popular Weigh Down Workshop, which gave way to her establishing Remnant Fellowship Church, based on a literal, evangelical interpretation of the Bible. In LuLaRich, we learn that LuLaRoe’s founders DeAnne and Mark Stidham are Latter-Day Saints—and Mark Stidham was even noted as proclaiming passages from the Book of Mormon during a companywide sales event.

Both docuseries brought to mind for me a familiar religious environment often described as cult-like—the Christian megachurch. You’ve probably heard some of these churches’ names: Hillsong, Elevation, Churchome, Bethel, Mosaic, Vous, Zoe. By many, megachurches are understood to be Protestant or evangelical Christian congregations with unusually large weekly attendance and/or online followings.

Similar to both Remnant Fellowship and LuLaRoe, and often noted as a defining factor of cults, megachurches are typically characterized as having a considerably charismatic leader (or leaders) whose personality, in many cases, is bigger than the organization itself. This popularity can sometimes give way to megachurch pastors building connections with some of the world’s biggest celebrities. For example, this past summer, Churchome’s lead pastor Judah Smith joined his friend and congregant Justin Bieber on stage during 1DayLA’s Freedom Experience live concert event at Inglewood, California’s SoFi Stadium.

Vous Church lead co-pastor Rich Wilkerson Jr. with Virgil Abloh

That brings me to the podcast episode I recently listened to titled, “The Cult of Celebrity Megachurches.” Sounds Like a Cult is a podcast, hosted by Amanda Montell, the author of Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, and Isa Medina, a documentary filmmaker and comedy writer, that analyzes the cultishness of key cultural groups in the United States, such as astrology and SoulCycle.

In the particular podcast episode I listened to, they invited on special guest Grace Baldridge, a musician and documentarian behind Refinery29’s “State of Grace” series, which tackles faith, queerness, and American culture, to discuss the wave of celebrity megachurches, which, as they describe in the episode description, “use Silicon Valley-savvy marketing, celebrity endorsements, charismatic pastors, and a slew of doubtlessly culty recruitment techniques and power structures in an attempt to make Christ ‘cool’ for masses of modern young people.”

The episode was insightful, especially in considering how pivotal marketing is in the establishment, maintenance, and growth of megachurches—and it took me back to my college honors thesis project in which I observed and analyzed how megachurches communicate their message and represent themselves online. Now, as a 27-year-old man, I don’t attend any church, nor do I follow any traditional evangelical Christian practices; however, at the time of beginning to write my thesis seven years ago, I had been attending one of the United States’ largest megachurches, Elevation Church, for years prior.

Elevation Church’s Matthews campus in Charlotte, North Carolina, was right down the street from my high school, and, in many ways, served as my introduction to living out my faith. I would attend weekly worship services with my friends, invite my family to come even though my mom hated how loud the music was, volunteer as a greeter, and I was even selected to be one of the 12 high school participants in Elevation lead pastor Steven Furtick’s discipleship group where every few weeks he would spend dedicated time with us to share a message and answer questions about Christian growth.

Once I arrived at college, I immediately joined with a friend and tried to start a satellite Elevation Church worship service in the common room of one of our dorm buildings where we’d stream Steven Furtick’s sermons and blare music from Elevation’s popular worship band, Elevation Worship. When an Elevation campus opened an hour away in Raleigh, North Carolina, we would caravan students to and from worship services weekly.

Therefore, when I was tasked with coming up with a topic for my honors thesis, writing about megachurches was a no-brainer—and then bringing in my strategic communications major, as well as knowing lots of megachurches streamed their services online or shared them via podcast amassing huge online followings along the way, I thought it would be interesting to explore how megachurches portray themselves online.

In my study, I focused on four North Carolina megachurches—selfishly, Elevation being one of them—and conducted site visits, interviewed staff members, and analyzed content on the churches’ websites and Facebook pages to see what they offered on stage, how they talked about themselves off stage, and what they broadcasted online. I concluded that megachurches represent themselves as brands with their own unique identities and portray themselves as active, accessible, evangelistic, and supportive of spiritual growth with the goal of maintaining their traditional message while “breaking down barriers” that might keep people from being receptive to that message.

Screenshot of Mosaic Church’s clarity score on Church Clarity

In revisiting my thesis and the overall topic of how megachurches represent themselves online, inspired by Sounds Like a Cult’s discussion on the topic, I recognize something I was not ready to reckon with at the time is how megachurches’ marketing is rooted in deception through branding. Well-documented at this point with the help of groups like Church Clarity and Do Better Church is how popular megachurches, such as Hillsong and Mosaic, portray themselves online and in person as places where everyone is welcome while not disclosing their actively enforced policies barring queer people from staff and leadership roles.

In cult-like fashion, many megachurches and evangelical Christian organizations bait people into trial and membership through proclamations of purpose and belonging from an aspirational leader and a group of people who seem shaped in their leader’s likeness. You come for the opportunities for spiritual growth and community and then, because there are so many ways to be involved and there’s a pressure to be constantly involved, you become further engulfed by the organization until your social circle, calendar, and even sometimes your profession are entangled within the organization.

All the while, you’re regularly giving money to the organization through tithes and offerings, discouraged from thinking critically about the organization because critics either “don’t understand” or they’re “just upset,” and encouraged to engage with people outside of the organization almost solely from a place of recruiting them to join the organization.

People relinquish their entire selves to these organizations, which is why megachurches’ deceptive marketing practices are incredibly harmful, especially for queer people. To feel powerfully connected to an organization, so much so that you want to increase your involvement with that group from being an attendee to becoming a volunteer, staff member, or church leader, and then finding out that organization has undisclosed policies against you fulfilling one of those roles because of your sexual orientation or gender identity can feel like a violation—like your whole world is crashing down.

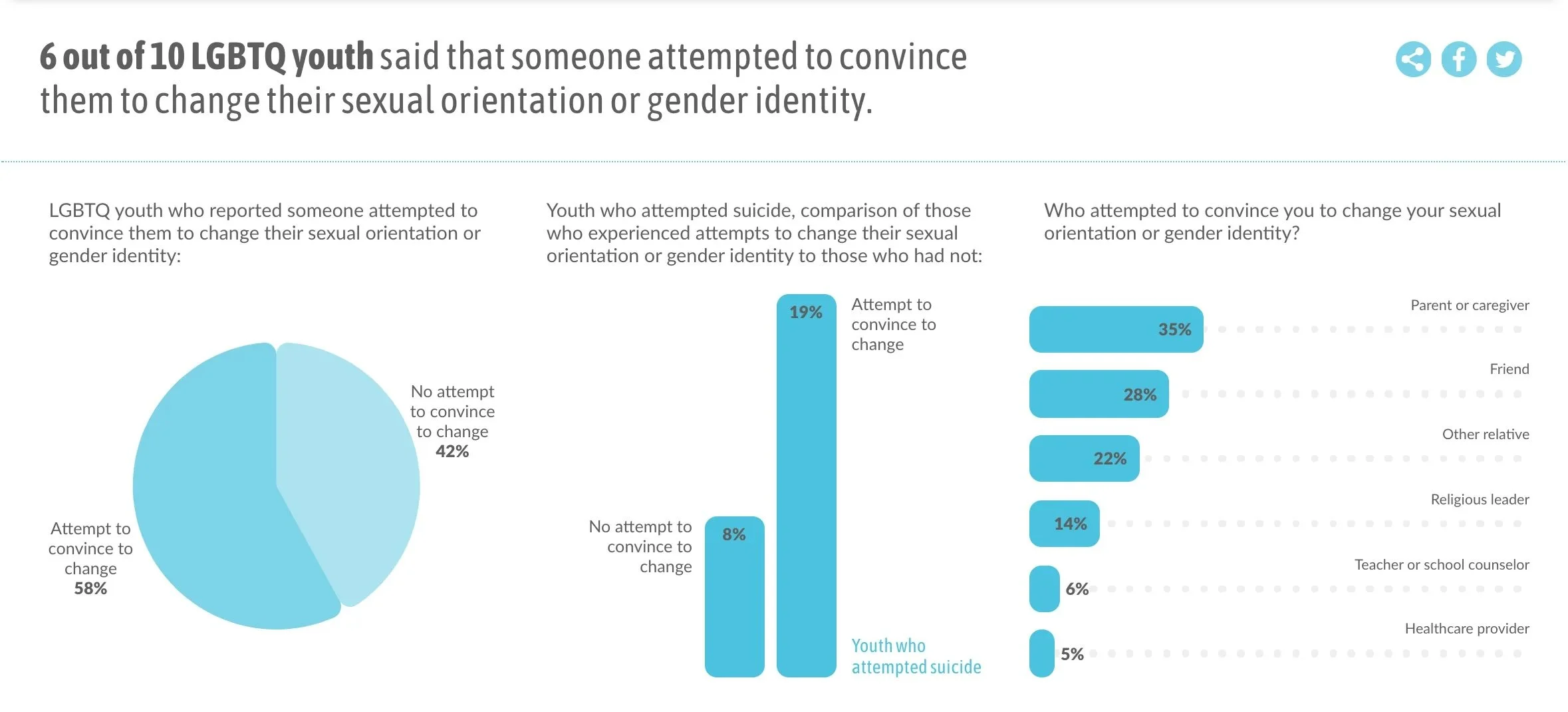

According to last year’s Trevor Project National Survey on LGTBQ Youth Mental Health, in which they surveyed over 40,000 LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 across the United States about the unique challenges they face every day, six out of 10 LGBTQ youth said that someone attempted to convince them to change their sexual orientation or gender identity. Forty percent of respondents seriously considered attempting suicide in the year prior. Nineteen percent of youth who attempted suicide also experienced attempts to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, compared to 8% of youth who did not—and while family and friends had the highest rates of attempting to convince LGBTQ youth to change their sexual orientation or gender identity, religious leaders were also among the highest percentages.

The cost of rejection for queer folks is high, significantly aided by a lack of acceptance from within religious organizations. Through megachurches’ willingness to hide their most traditional and non-affirming aspects in order to appeal to as many people as possible, they’re not just breaking down barriers; they’re breaking down people—and deceiving well-intentioned seekers along the way.

As someone who joined megachurches and evangelical Christian organizations with genuine intentions to grow spiritually and help others, I had no idea about the depths of harm caused to queer people through religious organizations, or that the group I was signing up for was actively complicit in causing that harm. What I interpreted as love and acceptance actually turned out to be smoke and mirrors.

In leaving those environments, while my losses were significantly less than that of many of the queer people I know who also left, exiting came at a cost—as is the case with most cultish groups. The dynamic of many of the relationships I had with people still involved in those groups changed to where that relationship either faded or I became someone to them who had fallen away, prompting questions of, “How are you, really?” What once felt like my entire world became past experiences I’ve spent years since trying to unpack.

At one point in my thesis project, I wrote, “As the years go on, it can be predicted that megachurches’ communications methods will change in order to stay relevant with the times.” While that’s true, if at their core, megachurches and religious organizations continue to be focused on growing their empires at any cost, even if that means deceiving people who are most in need of affirmation and acceptance, they will continue to cause serious harm, especially to queer people. They also can’t be surprised when those who see through the facade accuse them of being cults.