Cypher Pt. 2: Cole, Alex, Koku & Julius

Love Letters on Departure Albums

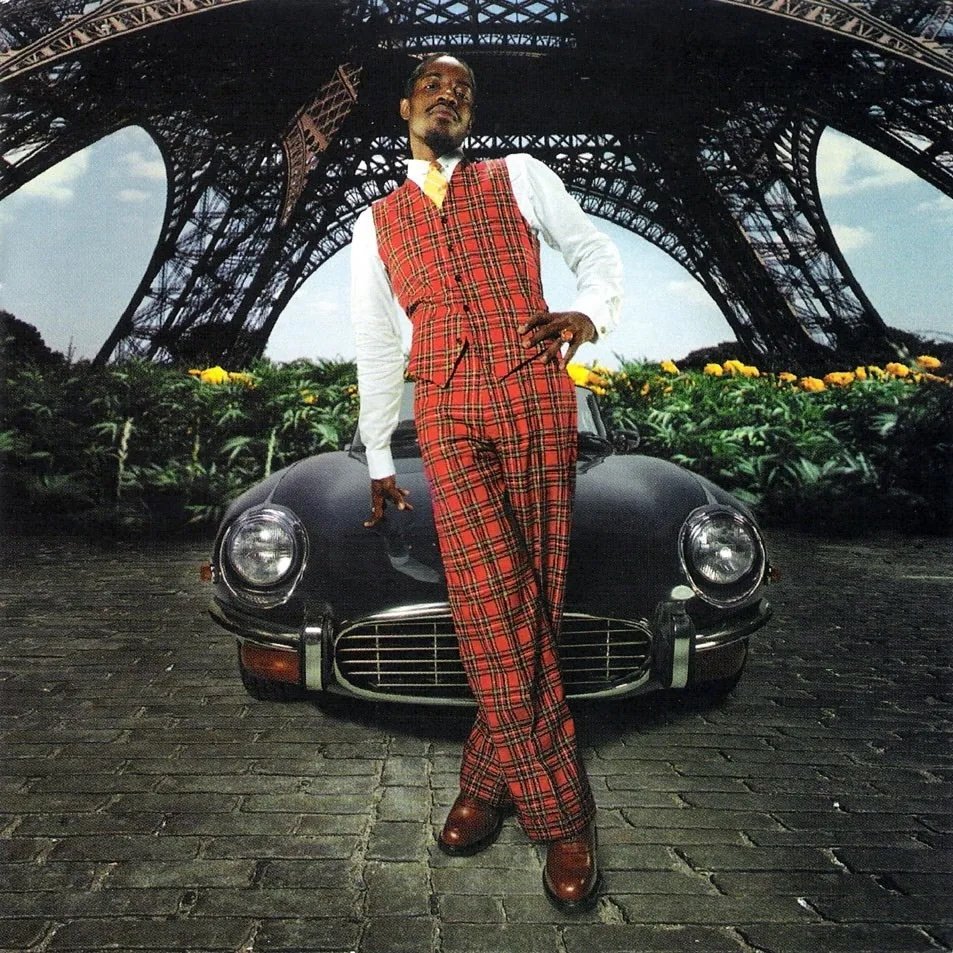

Photo by Kwame Brathwaite (Art Institute of Chicago)

Writing Boys—Alex Lewis, Cole Henderson, Julius Tunstall & Koku Asamoah—is a community focused on writing for ourselves and each other. Last year, in our first installment of “Cypher,” we wrote love letters to one another about growing up as Black men raised by Black men. This project was inspired by “Echo,” an essay co-authored by Kiese Laymon, Mychal Denzel Smith, Darnell Moore, Marlon Peterson & Kai M. Green from Laymon’s book, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. This year, we write about departure albums.

Cole

Dear Alex,

Departure. It’s an anxious word, don't you think? It means to leave and go on a journey. No matter how prepared you are to leave, you’re uncertain about what lies ahead. The act requires change. It requires you to say goodbye to your past and hello to your future. Even when you know it’s time to get up and leave, it still takes courage to move on from a place of rest because sometimes we become comfortable in our turmoil.

A departure is needed when the rhythms of life become the beat that we operate under, often monotonous. To break away from the redundancy, we need a new time signature, a different sound, and collaborators to lend a hand on our path. So, it’s very fitting music artists should call albums where they’ve drastically deviated from their familiar sound departure albums.

This year might be the year of the departure album. Some noteworthy music artists took leaps of faith and decided to experiment with sounds that listeners felt were unknown to them. Earlier this year, Lil Yachty released the psychedelic rock album Let’s Start Here, Janelle Monáe tapped into reggae and Afropunk with her release of The Age of Pleasure, and André 3000 performed woodwinds for 86 minutes with his debut solo album, New Blue Sun. Our beloved JT said it best, “I feel like there are multiple levels to departure albums, but specifically a sonic shift is a big part, but you gotta think about, like, people working with a different producer…I think that there's so much to it like different sounds, different bands, and different band members…” When music artists decide to do this, I like to think that it’s not an act of defiance, but instead, it’s an act of liberation. Even if the project is rooted in rebelliousness, there must be a foundation of self-love, which in its own right can feel rebellious. During an interview, André 3000 had this to say about his new album: “I Swear, I Really Wanted To Make A ‘Rap’ Album But This Is The Way The Wind Blew Me This Time.” It’s important to note that one must first shed the existential weight before being taken by the wind. That’s self-love and liberation.

Source: Chris Maggio

The band Toro y Moi’s album Sandhills is the departure album that did it for me this year. Okay, it's an EP, but I think that’s why I love it even more – like a staycation, where you have the freedom to explore places within your intimate surroundings without the fatigue of the long travel. And that’s just what Toro y Moi’s Chaz Bear did, as the EP documents his return to his hometown of Columbia, South Carolina. Sometimes, we’re not fond of going back home – there’s a reason we left in the first place. When we go back, we get transported to our trauma, the old you. We are forced to navigate the awkwardness, the conversations that end with an agreement to disagree. It’s almost always worse in our minds than in reality, but it’s sobering to experience home with a new heart.

Typically a Chillwave artist, Chaz tackles more of an Americana/country sound on Sandhills. Chaz sings on the opening track, “I didn’t tell anyone I was comin’ home, and I stayed for three months/Spent the summer in South Carolina, doin’ what I want.” Chaz, now based in Berkeley, California, grew up in the South. We’ve all spent time beneath the Mason-Dixon line and written about home in one form or another. We all have a Southerner alter ego within us, whether it’s with an MD flavor or NC. “This is from the perspective or the lens of a Southerner who’s left the South, but is still in love with the South. It’s from a contemporary perspective. It’s not really from a youthful [lens], but it’s more of a reminiscing writing about home.” says Chaz in an interview with publication American Songwriter. I understand that our love and care don’t represent the idea of the traditional South, and that’s okay. When we write, our collective voices ring to impact those who look like us, feel like us, and think like us.

I’ve been in Burlington, North Carolina, longer than I lived in Queens, New York. I’m departing from the idea that I’m a Yankee transplant. I’m a Southerner, and it’s my home. I met my wife here, I met JT here, and because of JT, the connection has allowed me to feel at home with you and Koku. My hope is that I can abandon the idea that I don’t belong where my feet are. Just because you depart from a place, doesn’t make the old or new place any less of your home.

Chaz replied to a question about where he feels most at home, “I feel at home probably equally in both. I do, in my mind, live in both places. I might visit one less than the other, but I have family and I have friends still in South Carolina that I call daily. So yeah, I feel like home isn’t necessarily one location, but I’m actually starting to feel at home everywhere.”

I’m proud of JT for making Asheville his home. I’m proud of you, Alex, for the courage to buy a home. And I’m proud to call Koku a homie as I catch glimpses of his hospitality, which makes us all feel at home. As we depart to our different places during this holiday season, take solace in knowing Writing Boys is a home for you and a support system while departing. We’re all on this ride with you, awaiting you on your arrival.

Alex

Dear Cole,

When we all wrote letters to each other last year, me and you hadn’t really spent any time together yet. I remember JT introducing my wife and I to you and yours on a street corner in Greensboro. Writing this now, I’m just getting home from kicking it with you and JT back in Greensboro. I told you my letter was going to be about André 3000, and you were so excited to see how it would come together. You made me even more delighted to write it.

Departure doesn’t elicit anxiety for me as much as it evokes readiness. Whenever I travel, I aim to make the most of it. But there’s always a time toward the end when I’m ready to be home. I’ll miss my people, but nothing sounds better than putting on sweats and cozying up on the couch. Even as I think about past instances of leaving jobs or moving across the country, I knew the time had come. That the change I needed was on the other side. Oftentimes, we’re already moving in that direction.

Throughout his career, André 3000 has been characterized by his changes. These pivots have shown up in the music he makes, the art forms he chooses to attempt, and even the clothes he wears. Fans have attributed his evolution in fashion to Erykah Badu, a futurist in her own right who dated André in the mid-90s and is also the mother of their son, Seven. “People like to joke about Erykah Badu, the mother of my child: ‘Oh, you completely changed,’” André told Jon Caramanica for The New York Times. “I was on my path before I even met Erykah.”

On “A Life in the Day of Benjamin André (Incomplete),” André’s outro on Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, he raps about him and Erykah:

“And on stage is a singer with some thing on her head

Similar to the turban that I covered up my dreads with

Which I was rocking at the time

When I was going through them phases trying to find

Anything that seemed real in the world”

André was already searching for who he would become. It’s hard to disentangle departures from arrivals. In some cases, they are one in the same. Idlewild aside, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below currently stands as OutKast’s final album and the best-selling rap album of all time at that; however, it’s technically two solo albums—a departure from Big Boi and André 3000 rapping together on most of their songs. André hardly even raps on The Love Below; he sings, trading in punchlines for melodies.

I wrote about it in a recent essay where I touched on lessons I’ve learned from André 3000 making a woodwind album, but a classmate gave me Speakerboxxx/The Love Below for my birthday in third grade. At the time, I remember being drawn to the singles I’d hear on the radio, “The Way You Move” and “Hey Ya!” Big Boi’s “GhettoMusick” was even part of the NBA Live 2004 soundtrack. But once I got my hands on the album, I almost strictly listened to The Love Below. Still, I consider that half of the record to be one of my all-time favorite albums.

Questlove posted about New Blue Sun on Instagram and described it as a departure album, “albums the complete opposite of what the artist is known for.” He also called it a “welcome introduction.” This is how I understand The Love Below. André 3000 broke away from how we understood OutKast and his role in the duo, while he invited us to gain a clearer picture of who he is and what his influences are. André also gave us a sneak peek of where he was going. “The strive for independence is evident,” wrote Mr. Wavvy for Okayplayer, “[André] can be found playing a handful of instruments over the course of the 20 tracks.” New Blue Sun didn’t happen in a vacuum; it was always in the making—whether we or André realized it.

The beauty of closeness is we get to see things in each other before we realize them in ourselves. André 3000 reminisced, “I’m singing around the house, and Erykah’s like: ‘That sounds great. Why you not doing it?’” The Love Below reminds me we’re already on the path of where we’re going. Cole, you have a commitment to curiosity that will continue to show itself in beautiful ways. JT, you are gaining a deeper understanding of your power, which, paired with your talent and compassion, will cause your words to live in others’ spirits. Koku, people can’t seem to make sense of your generosity, but you’re helping us see care for care’s sake is required for the world we desperately need.

“We met today for a reason,” André sang on “Prototype.” He continued, “I think I’m on the right track now. I think I’m in love again.” Thank you for being where I return, where I know love resides, my right track, my “real in the world.” I make the art I want to make because you give me permission to do so. All I hope is that I can be your Speakerboxxx, your other side, the Erykah helping you find your way—which is to say, I want to keep doing this together even as the realities of life maintain some level of distance between us.

I want to say stank you very much for picking me up and bringing me back to this world.

Koku

Dear Cole & Alex,

Where do we go after a departure? Does the intended route always lead to a positive outcome? That may not always be the case in the sense of public appeal. But when looking at oneself, departing from the comparative norm of their laid groundwork may just be what's needed to continue. But what if that still isn’t enough? What if there was still untapped potential as self-reflection sets in? Alex, Cole, and JT, we set out to write about departures, and Cole, you stated it best when you said, “A departure is needed when the rhythms of life become the beat that we operate under, often monotonous.” But coming back to who we are can be just as liberating.

As I grow into my late twenties, I can trace back a paper trail of many projects, songs, and ideas that have flooded my mind from my teen years up to now. Some of these objects of creativity will never see the light of day, and some of them have the potential to be great pieces of work if fully fleshed out. Sometimes I play my old beats and have to quote Phonte from Little Brother and say, “Thought I left the shit I used to listen to / 'Til one day, I was playing my old shit like / ‘Who the fuck is this? I kind of miss this dude,’” because I see the potential of what could have been.

Common is one of my favorite artists of all time, and throughout his career, he has undergone many changes. His debut album, Can I Borrow A Dollar, was a departure from rap at the time and would be the blueprint for his later projects. Featuring jazzy samples, classic drum breaks, and an undeniable West Coast influence that would ultimately play an interesting role in his career that, although did not directly inspire his later beef with Ice Cube, I can’t help but feel it was an added contributing factor. I also want to add that Common had this high inflection at the end of most of his bars that, as far as I know, started and ended on this project, thankfully so because although the album was a great showcase of rap, we can see Common still had room to grow. And we would all see a new version in his project, Resurrection.

Two years later, Common released Resurrection. Here, we see Common at his core, with production mostly handled by No I.D., say for two tracks handled by Ynot. Resurrection can be seen as one of the biggest highlights of his career, with tracks like “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” a reminiscent look of Hip-Hop, and tracks like “Communism” where he addresses all the cartoony sounds he used to make. He crafted a lane for himself that fans grew to love, that is, until 2003 when one project left fans and critics divided at the time of its release.

Source: Hiroyuki Ito / Getty Images

At this point, Common had a couple of projects under his belt, One Day It Will All Make Sense and Like Water For Chocolate, both of which hold up to this day—the latter of which introduces production from J Dilla and late 90’s, early 2000’s supergroup Soulquarians—a group with an eccentric, neo-soul, earthy vibe. You know the type, think of the girl in college who listens to Erkyah Badu and carries crystals in her tote. Common’s rap style, being not so far off from the rest of his peers, made him a fit to join the group but also shifted his sound, making his album Electric Circus divisive amongst listeners. Filled with influences from rock, techno, electronic, pop, neo-soul, and more. This project was ambitious and considered a departure from his previous work. In retrospect, it does hold up; it shows a side of music many were only willing to tap into if it showed commercial success, but instead, Common truly crafted a circus of ideas and sound; no track sounds the same, which, on the one hand, gives you a ride that does not feel stale from beginning to end, but on the other hand, we lose the linear idea of what this album means and more importantly who Common is.

Coming off of Electric Circus, Common was hit with a dilemma while crafting his next album. He could either stay with a style he and his peers created or return to what he knew worked for his previous projects. Luckily, J Dilla had a close bond with Common, so much so that he would come to live with him in California while battling TTP (Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura) and Lupus. RIP J Dilla. Although working on Electric Circus as well, J Dilla’s production was still just as coveted as any top producer; alongside signing with Kanye West's label Good Music, the direction the album was taking even sounded promising to detractors of Electric Circus.

I got a lot of love for departure albums; Cole and Alex, you mentioned Chaz and André 3000, two artists with an already unique sound who could somehow differentiate even more. But what Common was able to do was a return to form, taking past ideas and sounds and offering a magnum opus of a project in the form of 2004’s Be.

What Electric Circus lacked in concept, Be picked up and elaborated in meaningful ways. He didn’t revert back to the sound of any previous album, Common brought a prolific version of himself that was always there. From an intense opening track filled with a slick bassline, electric synth, bombastic horns, subtitles piano keys, all layered on top of Albert Jones 1977’s “Mother Nature.” The song fills you with unknowing nostalgia; pair that with a verse that has Common reflecting on life and death, ultimately coming to an end by saying, “The present is a gift, and I just want to be.”

On the track, “They Say,” Common says, “They say my life is comparable to Christ, the way I sacrificed, and resurrected, twice.” I think this perfectly sums up what a departure can do for an artist, sacrificing what the audience may want to give them what’s needed. In Common’s case, the Electric Circus gave him what he needed. Without it, Be wouldn't exist, or I should say, what the album represented wouldn't exist. The album reflects on love, faith, authenticity, and fulfilling dreams. After Electric Circus and its reception, Common was left reflecting on these ideas with his back against which he could make something true to himself. An amalgamation of new and old ideas, not a departure, but a return to form.

Julius

Dear Cole, Alex & Koku,

Well, shit. Being a closer always gets me in my feels because I look up to every single one of you so fondly. It’s hard for me to even think about how I can follow y’all because the imposter syndrome is too real. This is only the third time I’ve published this year. Not because I didn't want to, I did, my life has just taken this weird turn and I gained some responsibilities, some I'm thankful for, some I regret. Which dictated what album I was going to choose and why.

Stevie Wonder didn’t have to renegotiate, but he did. He told Berry Gordy to write me up a new contract because I'm an adult and I have a lot more to say. He asked for full control over his music. No more "Motown sound" he wanted to create his sound.

To renegotiate with oneself creatively is to tear down the house and build a different structure. Departure is a word that I always thought was negative, but if you flip the script it also means you’re stepping towards something new and fresh. From a music critic’s perspective, I know that when people think about Stevie Wonder, and they think about his departure album, they would probably say Secret Life of Plants is THE one. I want to politely say everybody can shut the fuck up (respectfully).

Turning 30 this year, and getting a full-time job that requires a lot of my attention. My partner and I have opposite schedules. These things had me negotiate the contract of my own life and what it means to be a musician and creative. That is why I’m choosing Music of My Mind as my departure album.

Source: GQ India

March 3, 1972, Stevie's 14th album starts sonically different than anything he's created in the past. He calls on the creators of the ridiculous synthesizer unit TONTO, Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff, to help him expand his sound. It's no suprise when you drop the needle on this record it immediately takes you to a new world. A psychedelic talk box weaves in and out each speaker, while a pulsing synth bass grounds you into this trippy melt of funk, folk, and R&B. Twenty-one-year-old Stevie played every instrument on the album except some trombone and guitar. His first words on the record are:

"Listen, baby

Every day I want to fly my kite

Every day I want to fly my kite

And every day I want to get on my camel and ride, ooh yeah"

I'd like to think that my 30s are the beginning of my kite-flying era. I want to care less, without being careless. I want to choose my words carefully while speaking freely. I want to scream, laugh, and love ferociously. That’s my renegotiation with myself, as I depart from my 20s.

Cole, Alex, and Koku, I can't wait to go outside and fly a kite together, because like Stevie said when kicking off what critics call his Golden Era/Classic Period:

"And when the day is through, nothin' to do

I sit around grooving with you

And I say it 'cause I love having you around"

Love y'all.